Imagine sitting in a crowded stadium, with thousands of faces filling the stands. To you, no two are alike. In an instant you can pick out family and friends, spot a celebrity on the Jumbotron, and recognize each as an individual from nothing more than the patterns of their face. The ability to recognize faces has long been treated by scientists as a hallmark of large-brained animals. In primates, entire brain regions, such as the face patches of the inferior temporal cortex, are devoted to this task, with neurons that fire selectively to faces and little else [1]. Such specialization was thought to require the vast computing power of a mammalian brain. Yet, evidence from a small social insect challenges this assumption.

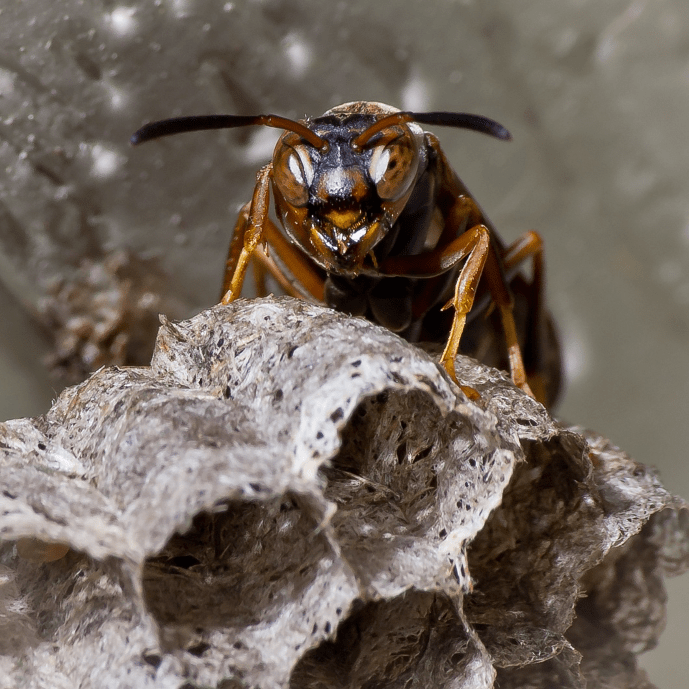

Paper wasps (Polistes) are common across the northeastern United States and Canada, where (to the dismay of many) they construct fragile, papery nests beneath building roofs and tree branches (Figure 1). Unlike honeybees, where a single queen monopolizes reproduction, Polistes colonies begin as collectives of females, each with the potential to become queen. The stability of the colony depends on the rapid establishment of dominance hierarchies, and this requires an ability to identify and remember rivals.

Elizabeth Tibbetts first demonstrated that Polistes fuscatus wasps solve this problem through facial recognition [2]. She noted that individual wasps bear distinct facial markings and reasoned that these might serve as identity signals. Through a series of elegant experiments, Tibbetts painted new patterns onto wasps and returned them to their nestmates. Unaltered, a familiar face was met without incident; altered, it was treated as that of a stranger, and dominance fights ensued. The finding was remarkable: insects, long thought to be reflexive machines, could recognize and remember individual faces.

But this evoked a deeper question: how does a miniature brain, containing fewer neurons than the retina of a human eye, accomplish what primates devote entire cortical areas to? Michael Sheehan, a former student in Tibbetts’s lab, and his postdoctoral fellow, Christopher Jernigan, began to approach this question. They found that socially enriched wasps developed larger brain regions such as the anterior optic tubercle [3], suggesting that social experience shapes neural architecture. However, the neural correlates of facial recognition remained elusive.

This mystery was tackled in a new study [4] by Sheehan and Jernigan, as well as collaborator Winrich Freiwald, who turned to powerful new tools. Using silicon probes with hundreds of recording sites (a dramatic departure from the single microelectrodes that once defined neuroscience), they recorded extracellular activity across multiple brain regions in wasps immobilized in front of a screen. They applied statistical methods called spike sorting to separate the jumble of electrical activity from each recording into signals from individual ‘units’, or putative neurons, of which there were nearly 800 in total. The wasps were shown looming stimuli, mimicking the threat of a rival, consisting of images including conspecifics with varying facial patterns.

The results were striking. Some neurons fired selectively to the faces of other wasps, especially when shown from the front, the perspective most relevant during agonistic encounters (Figure 2). These face-like “wasp cells” were most often found in the lateral protocerebrum, near the optic glomeruli (brain structures thought to be used for higher-order feature detection; [5]), though responses also appeared in mushroom bodies and other areas. A few neurons even exhibited a rudimentary form of view invariance, responding to the same individual across different angles, much like primate face cells. Yet the majority were tuned to the ecology of wasp life: rivals as seen head-on, not faces floating alone. Indeed, when presented with a disembodied face, the neurons fell silent.

More revealing was the behavior of ensembles. Using a classifier, or a computer algorithm that attempts to guess stimulus identity based solely on patterns of neural firing, the researchers found that the collective activity of these neurons carried information about individual wasps. In other words, the population response did not merely signal the presence of a face, but could, in principle, encode who that face belonged to. This discrimination vanished when the images were scrambled, confirming that the signal was specific to genuine identity-bearing features.

The picture that emerges is one of both convergence and divergence. Convergence, in that wasps and primates, separated by more than 600 million years of evolution, have both arrived at neurons tuned to faces. Divergence, in that the neural architecture is different: primates cluster their face cells into cortical patches, while wasps distribute theirs across multiple brain regions. Remarkably, the wasp face system may operate with only hundreds of neurons, highlighting the efficiency of small brains in solving computationally difficult problems.

How do face-responsive neurons change with social experience? What genetic programs underlie their emergence? Jernigan, now establishing his own laboratory at Wake Forest University with a prestigious “pathway to faculty” NIH K99/R00 grant, will undoubtedly follow these questions further.

Beyond wasps, this study signals a shift in how insect neuroscience can be approached. For decades, research in invertebrates emphasized intracellular recordings of single, identifiable neurons, and more recently genetic tools that are only available in a few model species. These approaches remain invaluable, but they risk missing the distributed, emergent computations that underlie cognition. Higher-density extracellular recordings, once confined to rodents and primates, are now revealing that similar techniques can also help elucidate the neural basis of behavior and cognition in invertebrates. Some recent advancements include the discovery of goal-direction cells in the central complex of migratory monarch butterflies [6]; contrast enhancement computations that separate overlapping odor signals in the locust antennal lobe [7]; and the neural correlates of octopus sleep [8].

What once seemed the sole domain of primates now appears to be a general solution to the demands of social life. That such complexity can be built from so few neurons reinforces the notion that brains evolve to meet the challenges of the societies they sustain. Faces are, after all, simply objects—arrangements of lines, colors, and contrasts. Yet our brains, and those of wasps, treat them as special. By uncovering how circuits extract these visual parameters to identify a face, we also see the broader principles of object recognition itself: how nervous systems transform visual features into meaningful social and ecological representations.

References

[1] Tsao, D. Y., Freiwald, W. A., Tootell, R. B., & Livingstone, M. S. (2006). A cortical region consisting entirely of face-selective cells. Science, 311(5761), 670-674.

[2] Tibbetts, E. A. (2002). Visual signals of individual identity in the wasp Polistes fuscatus. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 269(1499), 1423-1428.

[3] Jernigan, C. M., Zaba, N. C., & Sheehan, M. J. (2021). Age and social experience induced plasticity across brain regions of the paper wasp Polistes fuscatus. Biology Letters, 17(4), 20210073.

[4] Jernigan, C. M., Freiwald, W. A., & Sheehan, M. J. (2024). Neural correlates of individual facial recognition in a social wasp. bioRxiv.

[5] Keleş, M. F., & Frye, M. A. (2017). Object-detecting neurons in Drosophila. Current Biology, 27(5), 680-687.

[6] Beetz, M. J., Kraus, C., & El Jundi, B. (2023). Neural representation of goal direction in the monarch butterfly brain. Nature communications, 14(1), 5859.

[7] Nizampatnam, S., Saha, D., Chandak, R., & Raman, B. (2018). Dynamic contrast enhancement and flexible odor codes. Nature communications, 9(1), 3062.

[8] Pophale, A., Shimizu, K., Mano, T., Iglesias, T. L., Martin, K., Hiroi, M., … & Reiter, S. (2023). Wake-like skin patterning and neural activity during octopus sleep. Nature, 619(7968), 129-134.