Most people believe their beloved pet cat or dog is conscious, while others like to contemplate if artificial intelligence will lead to the downfall of humanity. But what defines consciousness, and which animals have it?

The separation of mind and body credited by the French polymath René Descartes had a profound impact on contemporary philosophy of mind. The dictum “cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) first conceptualized in 1637 is perhaps irrefutable, much unlike its seemingly logical extension suggesting mind–body dualism. Since then, amassing scientific evidence supports that processes of the mind are inexorably linked to the body, especially the brain—nature’s most complex organ. Often mistakenly assumed to be merely a vehicle of electrical signals, the brain exhibits remarkable plasticity, shaped by environmentally responsive and ever-changing patterns of gene expression, and bathed in a vast ocean cradling molecular transporters, hormones, and other modulatory agents. Our brains afford us behavioral complexity and a rich repertoire of thoughts, feelings, and emotions, and remarkably allow us to ponder their very existence. The human brain is overwhelmingly complex but exhibits deep ancestral similarities with those across much of the animal kingdom. Thus, the very biological substrates that give rise to these beautiful subjective experiences are ubiquitous in other organisms and share at least some functional similarity.

The current field of animal behavior and cognition was born from two competing schools of thought: behaviorism that was rooted in psychology, and ethology that stemmed from zoology. Behaviorists used carefully designed experiments to uncover how stimuli elicit responses, and ethologists studied natural behaviors (you might conjure a grayscale image of rats pulling levers for reward versus a sunny scene of ducklings trotting behind their imprinted caretaker). Together, this foundational work provided great insight into innate and reflexive (genetically encoded) behaviors, conditioning, learning, and how such traits might be passed to new generations [1]. In the pursuit of objectivity, most of these scientists were cautious to avoid ascribing human mental states to other animals, which oriented the field as a rigorous scientific discipline. However, such procedures were not universal. A pioneer of animal behavior, Jane Goodall, received great criticism for unconventional practices, such as naming subjects and using uniquely ‘human’ words to describe nonhuman animals. Goodall’s discovery of complex societies in nonhuman primates, defined by traits such as cooperative problem-solving, culture, tool use, personality, and emotion, informed her choice of words [2]. Whether it be an act of genius, empathy, defiance, or even imprudence, a new precedent was established: humans did not claim sole ownership of complexity, in behavior or mind.

But is this approach justified? After all, there remains skepticism that other animals even experience the subjective feeling of fear or pain, much less abstract thought or consciousness. Most human subjects used in psychological studies can verbally relay their thoughts, enabling their conscious experience to be accessible to an experimenter in real time. Perhaps unsurprisingly, other animals are unable to actively verbalize their thoughts, regardless if they exist. Furthermore, mental processes are very difficult to define, and animals (including humans) are more likely to excel in tasks that are relevant to the context in which they evolved. Thus, it is up to researchers to engage in careful observation and design clever experiments that allow an animal to ‘tell us’ what they may be thinking.

Such efforts have given us great insight into animal cognition. Other primates, our closest relatives, can infer the mental state of social partners [3], follow human gaze direction to an object of interest [4], and respond negatively to perceived inequity [5]. Remarkable feats such as these are not restricted to primates: elephants appear to grieve after losing a family member [6]; dolphins engage in complex play behavior using vocalizations and bubble rings [7]; crows can solve puzzles using concepts such as water displacement [8]; monitor lizards use long term memory to decipher foraging tasks [9]; archerfish learn how to precisely spit a jet of water to intercept different prey above the surface [10]; cuttlefish have episodic memory to remember ‘what, where, and when’ they have eaten [11], even delaying gratification for a better reward in the future [12]; and octopuses can learn how to solve tasks by watching a demonstrator [13].

An astute reader might notice all of these animals have relatively large brains, and subsequently wonder if comparable feats have been documented in animals with small brains. Despite having fewer neurons, the brains of many diminutive invertebrates like jumping spiders and bees are brilliantly dense and complex. Many brain cells exhibit profuse branching reminiscent of grand oak trees, which give rise to inconceivably large numbers of synapses, the locations at which cells communicate. The humble bee flying from flower to flower in your garden, once perhaps erroneously characterized as a ‘biological robot,’ can remember the locations of resource-rich flowers and communicate such locations to hive mates [14], learn to recognize human faces [15], improve upon an observed behavior [16], use tools [17], play [18], and possibly even count [19].

The feats described above resemble something we would consider to be ‘cognitive’ or ‘intelligent,’ and perhaps remind us of ourselves, but do these animals have any agency or subjective experience? In the scientific literature, the null hypothesis or status quo expectation when studying a clever animal defaults to the idea of cognitive parsimony [1], that simple instincts govern behavior. This perspective makes sense given the historical legacy of viewing humans and animals as different, or ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ organisms. Even humans, which reside above all other animals in the spurious “Great Chain of Being,” have some types of processing that can bypass conscious ponderance [20]. (Consider how some days feel like you are on ‘autopilot,’ performing actions without explicitly thinking about it.)

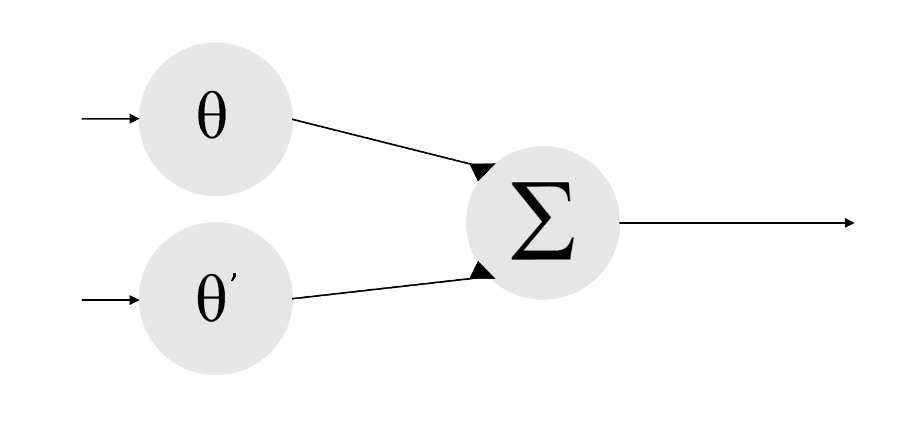

Furthermore, biologically inspired artificial intelligence can be programmed to reproduce surprisingly complex outputs with relatively simple internal architectures [21]. For a thought experiment, picture a simple neural circuit, a bunch of cells or nodes communicating with graded (analog) inputs to produce two alternative outputs (e.g., a static or receding object means ignore, while a rapidly approaching object means flee). A rigid structure would allow this circuit to always respond to a stimulus in the same way without any forethought. Our hypothetical mindless animal would be able to evade being eaten, one major barrier to passing down genes.

Figure 1. A simple neural network that decides to ignore or flee by combining information about object size and speed. A flee response will occur if the sum of the two inputs surpasses a particular threshold.

There are a virtually infinite number of ways to modify this circuit, simply by changing the connections between new or existing nodes or the strength of those connections. Perhaps a signal from elsewhere (the ‘stomach’) tells this circuit (in the ‘brain’) that our robot needs fuel, which might reduce the propensity to flee from a looming object that is potentially a food source instead of a predator. Real circuits controlling such decisions can be enormous, and intersect with other circuits across the brain, with their collective function being influenced by everything from an animal’s evolutionary history and environmental stressors during development, to specific stimulus properties, recent encounters with other animals, transient hormone fluctuations, hunger state, and so forth [22]. How might the relative importance of everything be decided computationally? It is indeed possible to mathematically model and predict many outputs given carefully selected inputs, but this can quickly become unwieldy to even conceive of without a ‘master regulator’ of sorts.

Consciousness is thought by some evolutionary biologists to be an adaptation for coping with a variable environment. Rooted in biology—flexible, sometimes even stochastic, but not deterministic. Not all cognitive behaviors need to be conscious, but consciousness might allow animals to be flexible in their responses to unpredictable conditions [23]. If key parameters of the environment are stored in working memory, such as temporary locations of food, animals can choose which aspects of the environment to selectively attend and respond to in accordance with their goals. Also consider pain, the mechanism of which is reasonably well understood: certain types of receptors (called nociceptors) detect tissue damage and send self-preservatory signals to the brain. These receptors, which are deeply evolutionarily conserved across the animal kingdom, can greatly benefit by subjectivity in some cases. For example, imagine you are about to eat a sizzling meal fresh from the oven. You might wait for the food to cool down before eating to avoid burning your tongue if you were relatively satiated, but if you were starving, the inconvenience of pain would be inconsequential. Your decision to take a bite has been informed by many different factors, including your hunger level, past experiences, and expectations about the future. Other animals make similar calculations. Even if pain increases proportionally with tissue damage, the amount of acceptable pain and tissue damage depends on the situation.

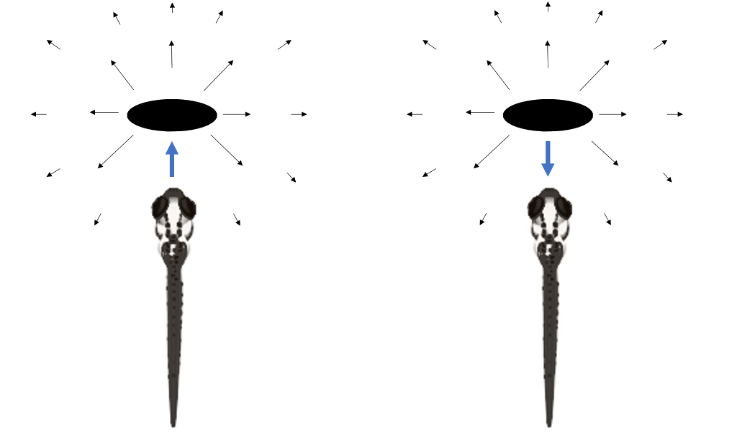

In a recent paper, the renowned cognitive neuroscientist Giorgio Vallortigara argues that the evolutionary origin of consciousness might have been the need for organisms to differentiate between external and self-generated motion, each of which produces identical sensory input [24]. In other words, consciousness might be useful for, or an emergent property of, the differentiation between the self and environment. To better understand this, imagine crouching to the floor. As you descend, the image of the hard pavement on your retina increases in size. This image is identical regardless if you are approaching the ground willfully, or the ground is approaching you. The latter is a much more dire situation. It is perhaps reasonable to speculate that the evolution of consciousness coincided with the evolution of eyes and vision, the sense most associated with the rapid diversification of fauna during the Cambrian explosion. However, it is notable that distinguishing between self-generated and external stimuli is important across modalities. (Are those my footsteps or another? Is that a predator touching my arm?)

Figure 2. The visual image of an object projected on a larval zebra fish’s retina is nearly identical regardless if the fish is approaching the object, or the object is advancing toward the fish. An ‘efference copy’ is encoded by neurons in the brain to anticipate sensory input generated by self-directed movement, separating actions chosen by the individual from the outside world. Vectors represent optic flow fields, or the pattern of visual motion (think how close objects seem to move faster than distant objects when you gaze out the window of a moving car.)

We currently do not have an acceptable theory of consciousness. While most people have an intuitive sense of the term, there is not even a consensus of what ‘consciousness’ is. The most recent attempt to define the term is “perceptual and affective experience or feelings, arising from the material substrate of a nervous system” [25]. A closely related term, ‘sentience,’ is usually defined simply as awareness. Research investigating this area is severely limited, but scientists have uncovered several modest clues. There are certain types of brain activity associated with conscious versus active sleep states (when you are dreaming, rapid eye movement sleep) in humans, of which are also shared by many other animals [26]. Some studies claim to have found neural correlates of consciousness, such as a specific type of neural response underlying sensory perception in carrion crows [27], but such interpretations remain contentious. The brains of many animals have cells with unique properties, such as so-called ‘mirror neurons’ that respond both when an animal performs a particular action or observes the same action being performed by another [28], which some speculate might be related to conscious experience.

Theory of mind, the capacity to ascribe different mental states to oneself and others, appears to exist in animals such as scrub jays that re-cache food items in private if another bird witnesses them hiding food [29]. Theory of mind develops during childhood in humans. Like us, many animals show evidence of experiencing emotions, including insects: bees demonstrate behavioral states consistent with ‘optimism’ or ‘pessimism’ [30], and fruit flies demonstrate an increased anxiety-like state after being injured, even after their wounds have healed [31]. Many animals demonstrate self-awareness, whether it be from mirror self-recognition tests [32] or an understanding of one’s own body dimensions [33], which is consistent with our own perceptual experience of consciousness.

The broader field of animal cognition is riddled with arguments, counterbalanced by two opposing forces—those that excitedly try to prove their favorite animals have abilities similar to humans, and those that relentlessly assert “simpler mechanisms!” For those that accept consciousness exists in other animals, of which are usually more closely aligned with the first camp of the false dichotomy, viewing consciousness as a sliding scale is tempting (i.e., humans are the ‘most’ conscious). This notion of ‘simple to complex’ is already dubious for other traits, but especially for those that derive from the mind. For example, there are working memory tasks in which animals such as chimpanzees dramatically outperform humans [34], and as mentioned previously, some human behaviors are guided subconsciously. For a more peculiar example, the limbs of the enigmatic octopus can, to some extent, function autonomously from the brain [35]. Clearly, a multidimensional framework that considers similarities and differences in an ecological and evolutionary context is needed [36], one that absolves traditional hierarchical or categorical thinking. Regardless if consciousness is an emergent property of highly dimensional data stored in massive ensembles of cells, or exists through mechanisms not yet known, we currently only have a vague idea of what to look for across species.

In 2012, many influential researchers across several fields participated in the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness, which unambiguously (and controversially) stated that nonhuman animals have nervous systems capable of giving rise to consciousness. The goal of this declaration was to shift modern thinking from ‘if’ other animals have consciousness, to ‘what’ forms consciousness can manifest across different types of animals. It is critically important that we overcome the taboo shrouding animal consciousness and reconcile the dearth of research addressing this subject, not just because our basic understanding of ourselves and the natural world is lacking, but because many aspects of society are based on cognitive parsimony.

Are ‘embodied’ or purely sensory explanations for complex behavior in comparatively simpler animals actually different than cognitive or ‘higher’ explanations in humans? I do not believe there is currently sufficient evidence to say which animals are conscious, nor do I believe there exists an infallible method currently available for its study. But when studying the mind, I do believe we should at least be skeptical of the tradition of human exceptionalism. Humans are incredible, after all—but many other animals are too.

I wish to leave you with a departing question: which is more problematic—ascribing human mental states to other animals, or defaulting to the assumption that only humans experience them?

References

[1] Waal, F. (1999). Anthropomorphism and anthropodenial: consistency in our thinking about humans and other animals. Philosophical Topics, 27(1), 255-280

[2] Goodall, J. (2010). Through a window: My thirty years with the chimpanzees of Gombe. HMH

[3] Flombaum, J. I. & Santos, L. R. (2005). Rhesus monkeys attribute perceptions to others. Current Biology, 15(5), 447–52

[4] Rosati, A. G., & Hare, B. (2009). Looking past the model species: diversity in gaze-following skills across primates. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 19(1), 45-51

[5] Neiworth, J. J., Johnson, E. T., Whillock, K., Greenberg, J., & Brown, V. (2009). Is a sense of inequity an ancestral primate trait? Testing social inequity in cotton top tamarins (Saguinus oedipus). Journal of Comparative Psychology, 123(1), 10

[6] Bradshaw, I. G. (2004). Not by bread alone: Symbolic loss, trauma, and recovery in elephant communities. Society & Animals, 12(2), 143-158

[7] Kuczaj, S. A., & Eskelinen, H. C. (2014). Why do dolphins play? Animal Behavior and Cognition, 1(2), 113-127

[8] Taylor, A. H., Elliffe, D. M., Hunt, G. R., Emery, N. J., Clayton, N. S., & Gray, R. D. (2011). New Caledonian crows learn the functional properties of novel tool types. PloS one, 6(12), e26887

[9] Cooper, T. L., Zabinski, C. L., Adams, E. J., Berry, S. M., Pardo-Sanchez, J., Reinhardt, E. M., … & Mendelson III, J. R. (2020). Long-term memory of a complex foraging task in monitor lizards (Reptilia: Squamata: Varanidae). Journal of Herpetology, 54(3), 378-383

[10] Newport, C., Wallis, G., Temple, S. E., & Siebeck, U. E. (2013). Complex, context-dependent decision strategies of archerfish, Toxotes chatareus. Animal Behaviour, 86(6), 1265-1274

[11] Jozet-Alves, C., Bertin, M., & Clayton, N. S. (2013). Evidence of episodic-like memory in cuttlefish. Current Biology, 23(23), R1033-R1035

[12] Schnell, A. K., Boeckle, M., Rivera, M., Clayton, N. S., & Hanlon, R. T. (2021). Cuttlefish exert self-control in a delay of gratification task. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 288(1946), 20203161

[13] Fiorito, G., & Scotto, P. (1992). Observational learning in Octopus vulgaris. Science, 256(5056), 545-547

[14] Menzel, R. (1999). Memory dynamics in the honeybee. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 185(4), 323-340

[15] Dyer, A. G., Neumeyer, C., & Chittka, L. (2005). Honeybee (Apis mellifera) vision can discriminate between and recognise images of human faces. Journal of Experimental Biology, 208(24), 4709-4714

[16] Loukola, O. J., Solvi, C., Coscos, L., & Chittka, L. (2017). Bumblebees show cognitive flexibility by improving on an observed complex behavior. Science, 355(6327), 833-836

[17] Mattila, H. R., Otis, G. W., Nguyen, L. T., Pham, H. D., Knight, O. M., & Phan, N. T. (2020). Honey bees (Apis cerana) use animal feces as a tool to defend colonies against group attack by giant hornets (Vespa soror). PLoS One, 15(12), e0242668

[18] Dona, H. S. G., Solvi, C., Kowalewska, A., Mäkelä, K., MaBouDi, H., & Chittka, L. (2022). Do bumble bees play? Animal Behaviour

[19] Howard, S. R., Avarguès-Weber, A., Garcia, J. E., Greentree, A. D., & Dyer, A. G. (2019). Numerical cognition in honeybees enables addition and subtraction. Science advances, 5(2), eaav0961

[20] Lundström, J. N., Boyle, J. A., Zatorre, R. J., & Jones‐Gotman, M. (2009). The neuronal substrates of human olfactory based kin recognition. Human brain mapping, 30(8), 2571-2580

[21] Peng, F., & Chittka, L. (2017). A simple computational model of the bee mushroom body can explain seemingly complex forms of olfactory learning and memory. Current Biology, 27(2), 224-230

[22] Sapolsky, R. M. (2017). Behave: The biology of humans at our best and worst. Penguin

[23] Chittka, L. (2022). The Mind of a Bee. Princeton University Press

[24] Vallortigara, G. (2021). The rose and the fly. A conjecture on the origin of consciousness. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 564, 170-174

[25] Irwin, L. N., Chittka, L., Jablonka, E., & Mallatt, J. (2022). Comparative animal consciousness. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience, 122

[26] Ehret, G., & Romand, R. (2022). Awareness and consciousness in humans and animals–neural and behavioral correlates in an evolutionary perspective. Frontiers in systems neuroscience, 16

[27] Nieder, A., Wagener, L., & Rinnert, P. (2020). A neural correlate of sensory consciousness in a corvid bird. Science, 369(6511), 1626-1629

[28] Heyes, C. (2010). Where do mirror neurons come from? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(4), 575-583

[29] Emery, N. J., & Clayton, N. S. (2001). Effects of experience and social context on prospective caching strategies by scrub jays. Nature, 414(6862), 443-446

[30] Solvi, C., Baciadonna, L., & Chittka, L. (2016). Unexpected rewards induce dopamine-dependent positive emotion–like state changes in bumblebees. Science, 353(6307), 1529-1531

[31] Khuong, T. M., Wang, Q. P., Manion, J., Oyston, L. J., Lau, M. T., Towler, H., … & Neely, G. G. (2019). Nerve injury drives a heightened state of vigilance and neuropathic sensitization in Drosophila. Science advances, 5(7), eaaw4099

[32] Kohda, M., Hotta, T., Takeyama, T., Awata, S., Tanaka, H., Asai, J. Y., & Jordan, A. L. (2019). If a fish can pass the mark test, what are the implications for consciousness and self-awareness testing in animals? PLoS biology, 17(2), e3000021

[33] Ravi, S., Siesenop, T., Bertrand, O., Li, L., Doussot, C., Warren, W. H., … & Egelhaaf, M. (2020). Bumblebees perceive the spatial layout of their environment in relation to their body size and form to minimize inflight collisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(49), 31494-31499

[34] Inoue, S., & Matsuzawa, T. (2007). Working memory of numerals in chimpanzees. Current Biology, 17(23), R1004-R1005

[35] Hochner, B. (2012). An embodied view of octopus neurobiology. Current biology, 22(20), R887-R892

[36] Birch, J., Schnell, A. K., & Clayton, N. S. (2020). Dimensions of animal consciousness. Trends in cognitive sciences, 24(10), 789-801