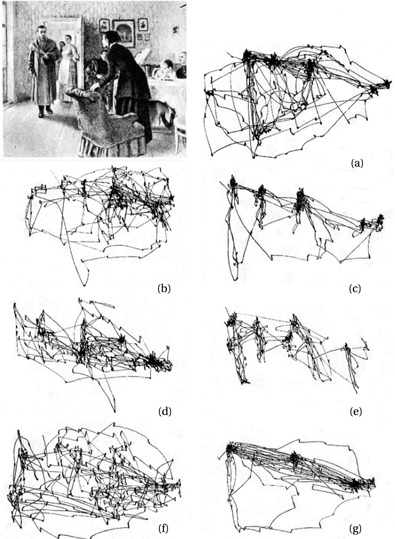

As you direct your eyes across this sentence, your foveae—small depressions in the center of each retina supporting the highest-resolution vision—focus on specific locations of interest. Given the amount of visual information available in our world is vast, it is impossible to process everything, making it necessary that behaviorally relevant information at any given time is prioritized over extraneous details. This was expertly demonstrated by Alfred Yarbus, whose book Eye Movements and Vision (1967) was among the first to emphasize how our goals and intentions shape where we look (Fig. 1). Eye movements and psychophysical studies have since been used to uncover the perceptual and cognitive processes that mediate visual attention in humans and some other vertebrates, but work with invertebrates is sparse by comparison (see Fig. 2). Decades of psychological research using human gaze direction as a measure of attention offer rich theoretical frameworks ripe for testing. For a recent review, see https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.12.001.

Jumping spiders have elegant, sophisticated, compact, and tightly integrated distributed visual systems. These spiders have eight camera-type (single lens) eyes arranged in four pairs located on the front of their cephalothorax (head). Their visual system is modular: the most forward-facing pair of eyes (principal eyes) is capable of remarkably high spatial resolution and color vision rivaling that of many mammals, while the rest of the eyes (secondary eyes) are hyperacute motion detectors with wide fields of view. First described by Michael Land in 1969, the principal eyes have small moveable (boomerang-shaped) retinas situated at the back of telescope-like tubes inside the head that enable the spider to inspect scenes and objects through saccades and scanning motions, directed by the secondary eyes. (Together, the secondary and principal eyes are functionally analogous to our peripheral and foveal vision.) Jumping spiders are active, diurnal, cat-like predators that visually stalk and pounce on prey, look for mates, and build and return to retreats in sheltered locations; however, our understanding of how jumping spiders use retinal targeting movements to obtain information selectively when exploring their environment or pursuing their behavioral goals is not well understood. Furthermore, our understanding of how jumping spiders process visual information is severely limited because neurophysiological experiments targeting their brains have historically been thwarted by their hydraulic locomotor system and the resulting internal body pressure. Only recently has this constraint been overcome, allowing neural recording techniques to be used in these animals. (For a recent review of what is known about visual processing in jumping spiders, see https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2023.09.002.)

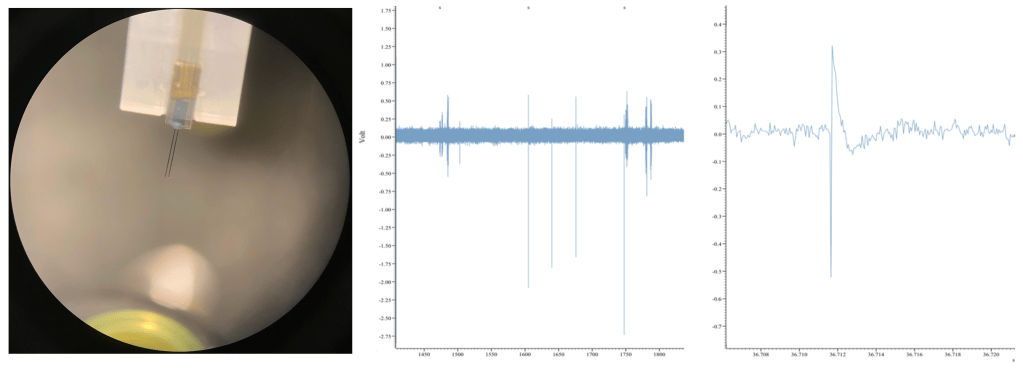

Currently, I am simultaneously recording eye movements (using a custom-built eye tracker; Fig. 3) and neural activity of various lower- and higher-order brain centers (using in vivo extracellular electrophysiology; Fig. 4) as well as high-pressure liquid chromatography in jumping spiders (Phidippus audax) as they respond to different types of stimuli and transition between behavioral states (Fig. 5). I am particularly interested in how these animals recognize and search for objects, and how their strategies and computations compare to humans and other animals. This work is in collaboration with Luke Remage-Healey at UMass Amherst and Ron Hoy at Cornell, and has received funding from the American Arachnological and Animal Behavior Societies.

During social communication, there is a dynamic interplay between vision, behavior, and various aspects of the environment. Mate choice is an example of an important ecological behavior directly affected by visual perception. Poetically captured in the writings of Elizabeth and George Peckham in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the theatrical courtship displays of many jumping spiders are adorned with striking traits such as iridescent scales and tufts of setae, which are presumably used as signals. Sexual polymorphisms present choosers with a challenge, as they must recognize conspecifics that exhibit divergent features. Several species of jumping spider in the genus Maevia feature more than one male morph. Maevia inclemens in particular exhibits an extreme case of male dimorphism in which each morph is characterized by profound phenotypic differences. To attract female attention, each male morph initiates a characteristic courtship display, one in a low posture presented close to the female and the other a tiptoe display from further away (Fig. 6). Each display features distinct signals (e.g., color or movement) that seem to target different eye types (Fig. 7).

Currently, I am investigating how females visually assess the components of each display as well as conducting mate choice, field, and population modeling experiments to offer a unique perspective into how choosers might facilitate the persistence of sexual polymorphisms and the evolution of elaborate traits. This work is in collaboration with Dave Clark at Alma College, and has received funding from an internal UMass dissertation grant.

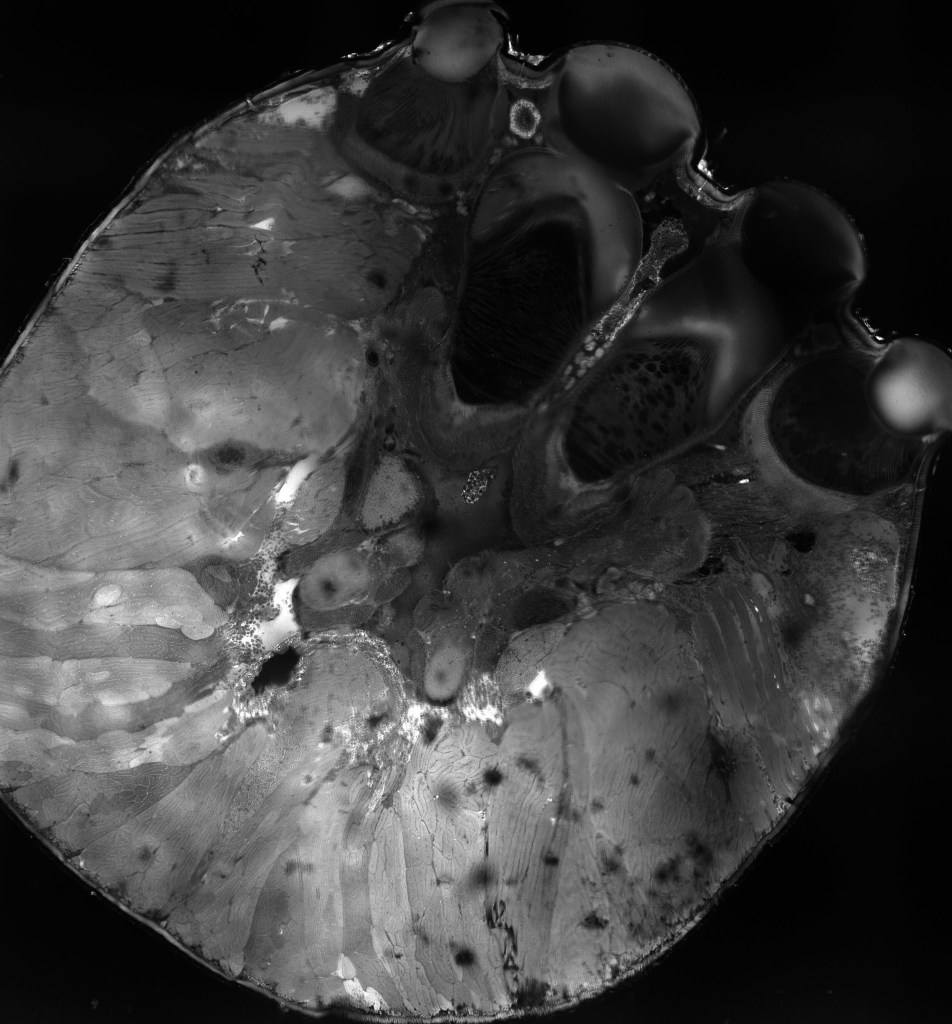

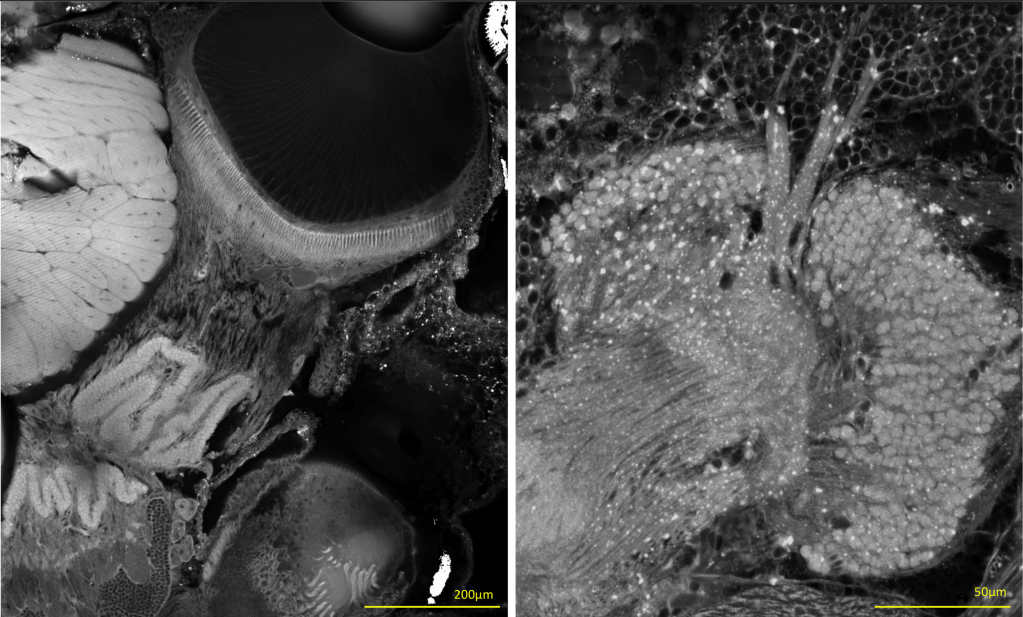

Eye designs and visual system architectures are exceptionally diverse in spiders (order Araneae), an ancient and speciose lineage of animals. Over the past 400 million years, spiders have evolved a striking array of lifestyles, behaviors, and ecological niches. Across families, their visual systems vary in the number of eyes and their arrangement, retinal movement capabilities (Fig. 8), eye anatomy and lens optics, receptor ultrastructure and physiology, opsin expression, neuromorphology, and the extent of vision-based behaviors. While similar in external appearance, the principal and secondary eyes of spiders have distinct evolutionary histories, internal structures, developmental pathways, and neural connectivity to higher brain regions. Interestingly, the distributed visual systems of spiders enable discrete visual functions to be distributed to one or more eye pairs (e.g., sensitivity to color, detail, depth cues, light levels, motion, or polarization). This potentially allows these animals to have much greater visual capabilities across more optical environments than their small size would suggest. For a recent review, see https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-23216-9_10.

Moveable eyes potentially offer animals a number of adaptive benefits: the ability to prevent retinal habituation, inconspicuously alter gaze direction, stabilize gaze during self-generated motion, increase resolution, and rapidly direct acute zones of the retina to locations of interest. However, the evolution of moveable eyes is poorly understood since eye movements have been most rigorously studied in vertebrates, a lineage that evolved moveable eyes only once. Jumping spiders independently evolved fine motor control over their principal-eye retinas and demonstrate tight cooperation between different eye pairs during visual tasks, but it is unclear to what extent this occurs in other spiders. My pilot data suggest that moveable eyes have evolved, been elaborated upon, and secondarily lost multiple times throughout their evolutionary history. Some clues for how this occurred might be gleaned from the secondary eyes, which exhibit variable organization in their visual pathways (one example shown in Fig. 9) as meticulously noted by zoologists like Bertil Hanström and Hans Homann in the early to mid-20th century.

I intend to later investigate how moveable retinas and the division of labor between principal and secondary eyes evolved across the order Araneae. To accomplish this, I will use phylogenetic comparative methods with ecological and lifestyle traits, quantitative behavioral assays and pose estimation (with DeepLabCut, a tremendously useful open-source tool), electrophysiology, ophthalmoscopic techniques, 3D printed tools, and confocal microscopy. Furthermore, I have successfully tailored fluorescence-based histological protocols (e.g., dextran injections for neural-tract tracing and immunohistochemistry using a broad panel of neural markers) used in other invertebrates.

I aim to develop molecular and genomic tools for jumping spiders. My long-term goals are to better characterize the development, connectivity, and physiology of different sensory organs and the brain (e.g., a brain atlas); develop neurogenetic, connectomic, imaging, closed-loop virtual reality, and computational tools; and study behavior and population dynamics in the field under natural conditions. I intend to help establish a species of jumping spider as a ‘model organism.’

For my postdoc, I intend to invest deeply in an established model system (e.g., C. elegans or Drosophila) using a circuit neuroscience approach to build skills and later help transfer tools. There are unique similarities between fly and spider nervous systems in particular despite their evolutionary split 400 million years ago, and many methodological and experimental approaches overlap.

Ongoing collaborations include Massimo De Agrò and Paul Shamble (biological motion perception); Min Tan and Daiqin Li (motion camouflage); Shimin Hu, Joonkoo Park, Randy Grace, and Fiona Cross (numerosity); Mariana Pereira (neuromodulators of behavioral state); as well as Olivia Harris (chromatic discrimination) and Jenny Sung (face perception) in Nate Morehouse’s lab.

Concluding Thoughts:

Jumping spiders are abundant worldwide and can be easily captured in the field or reared in large numbers in the laboratory. They readily exhibit natural behaviors in lab experiments, including gaze-shifting body and eye movements.

While eye movements for retinal stabilization to avoid motion blur are well-characterized, far less is known about how animals use gaze shifts to gather information from a scene. Precise methods of gaze tracking have provided unique and counterintuitive insights (e.g., see peahens: 10.1242/jeb.087338). While the moveable eyes of vertebrates and principal-eye retinas of jumping spiders offer tractable systems for studying the neural substrates and general rules of visual attention in distantly related taxa, the fixed eyes of many others (e.g., other arachnids and insects; but see 10.1038/s41586-022-05317-5) present unique challenges. However, many animals use body movements to shift their gaze direction (e.g., Fig. 10), which can be approximated, especially given excellent open-source tools like DeepLabCut are now available. Natural behaviors are usually accompanied by a combination of eye and body movements, which impacts visual processing (e.g., mice: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.033). More precise measures of gaze direction during behavior can allow for the comparative study of how animals use their vision to actively explore their environment, and how extended sequences of gaze movements are used to acquire specific information as animals pursue their behavioral goals. Remarkably, gaze direction can even be used during sleep as a powerful tool to study memory consolidation and REM-like sleep dynamics.

Similar to vertebrates, jumping spiders are capable of complex behaviors and cognitive tasks such as object recognition, visual search, learning, planning, navigation, decision-making, and problem-solving. Yet, these diminutive animals achieve such feats with far smaller brains composed of a fundamentally different organization. In at least some spiders, parallel processing clearly begins very peripherally, and thus offers an amenable system to study different visual pathways in isolation, which is difficult to achieve in other organisms. Work in this area will help us gain fundamental insights into visual processing, including how our own visual system works. The parallel visual systems of jumping spiders are also highly relevant for bioinspired technology, integrating ‘cheap’ broad-field motion detection with small, moveable, high-resolution focused sampling (examples here and here). Furthermore, the distributed visual systems of spiders might allow evolution to act independently on different pairs of eyes and their underlying neural pathways to help overcome functional trade-offs associated with eye design. Interestingly, the higher-order optic neuropils of spiders appear to be the primary brain regions that give rise to complex behavior and cognition. It has even been reported that macular-degeneration-like photoreceptor damage occurs in jumping spiders with poor diet (doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2023.10818) and advanced age, which appear to coincide with visuocognitive deficits.

Despite my emphasis on vision, other sensory modalities are very important to consider. In natural contexts, relevant sensory information is rarely constrained to a single modality. I am also investigating cross-modal interactions between visual, chemosensory, and auditory cues in jumping spiders. For example, I have found that cross-modal cues can alter retinal and locomotor activity during search tasks (Fig. 11), and there are cells in the protocerebrum that respond strongly to auditory stimuli. In collaboration with Mariana Pereira at UMass, I am using pharmacological manipulations and high-pressure liquid chromatography to investigate how key molecules in spider brains might be implicated in modulating sensory processing and behavior.

I am fascinated by the enigmatic sensory and perceptual worlds of animals. To understand how animals use their senses, my research integrates approaches across multiple levels of analysis, from molecules to the field.

Previous work:

Understanding how the psychology of predators shapes the defenses of colorful aposematic prey has been a rich area of inquiry. Warning signals that display the noxious condition of chemically defended prey often include visual cues, such as conspicuous coloration or patterns, which are readily learned by predators. The fields investigating predator psychology and aposematism have been dominated by studies of birds, which possess only a narrow range of the different sensory systems that have evolved. Warning signals are likely adapted to specific predators’ sensory systems, so more emphasis is needed on smaller understudied invertebrate predators and their interactions with comparatively sized prey. Recent studies with terrestrial invertebrate predators have been revealing surprising insights (e.g., some arthropod predators will ignore warning signals that birds respond to, and vice versa; see 10.1002/ece3.914 for an example). Found in nearly all of Earth’s terrestrial biomes, jumping spiders play key roles in regulating prey populations, which can have cascading effects on trophic interactions.

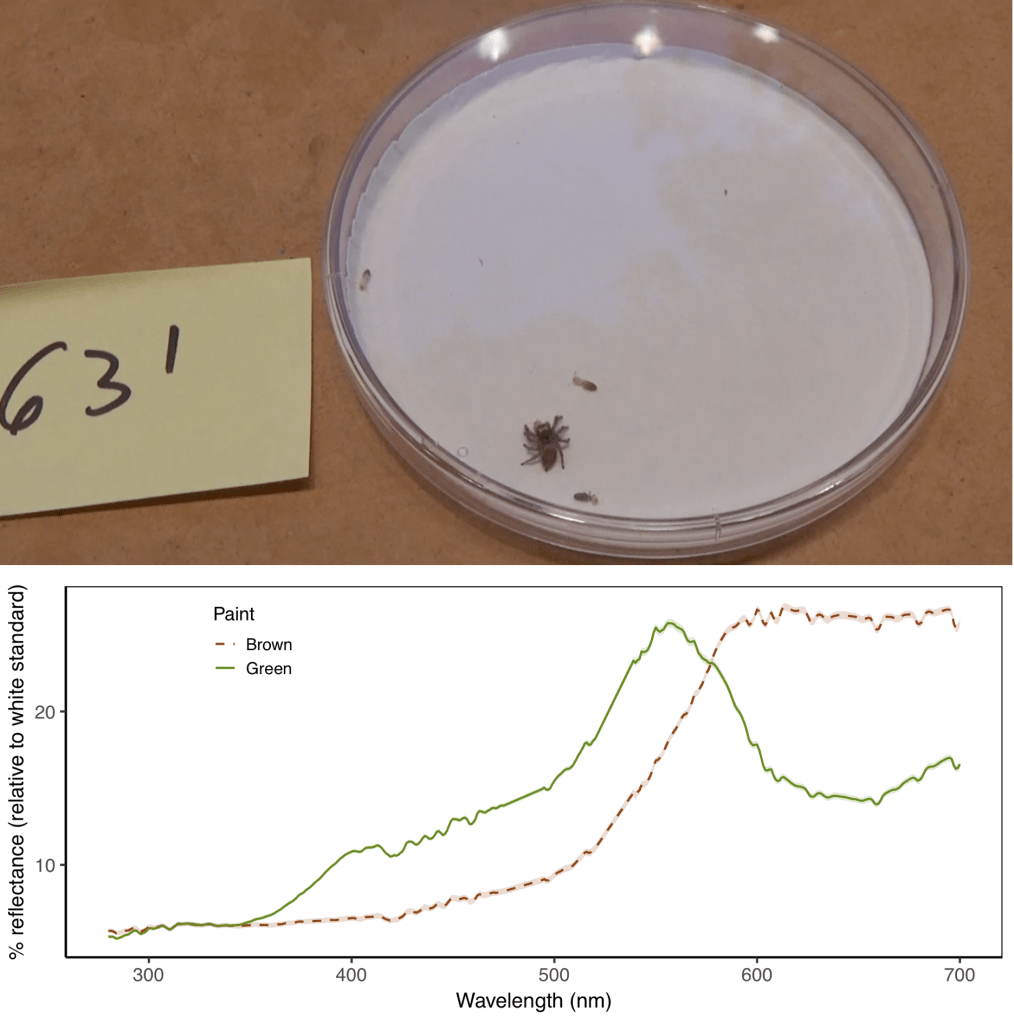

For my undergraduate research at the University of Florida, I used behavioral experiments to examine the scope for learning cues across different modalities in the context of foraging. Specifically, I directly manipulated aposematic signals (visual and gustatory) on prey items and tracked foraging decisions in the jumping spider Habronattus pyrrithrix (Fig. 12). Spiders can learn to avoid unprofitable prey items, and this can have important implications since learned associations might spill over into other contexts (e.g., mate choice). I am now using this behavioral assay to probe how learning changes representations of prey palatability in the jumping spider brain. This work was supervised by Malika Ihle and Lisa Taylor. Check out the culmination of my efforts here: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231205

All collected data, analysis scripts, and workflow are archived and publicly available in the Open Science Framework and can be accessed here: https://osf.io/w4n6k/. To learn more about open, reproducible, and reliable science, see Malika Ihle’s website. Here are some guidelines you can implement in your own work.